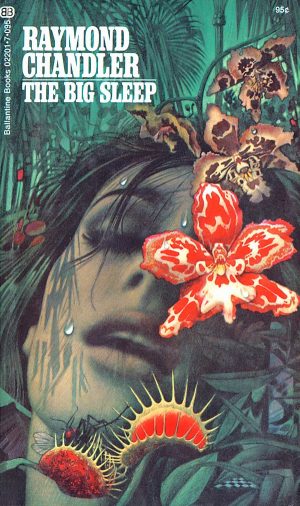

![TheBigSleep[1]](https://www.michaelakahn.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/TheBigSleep1-194x300.jpg) We’ve buried this classic American detective story in our final slot, but don’t worry, dear snob. It’s been anointed with holy oil of The Library of America. You can now purchase Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep in the fancy schmancy Library of America edition , and place it on your bookshelf in the “C’s” between your Library of America editions of the works of Willa Cather and John Cheever.

We’ve buried this classic American detective story in our final slot, but don’t worry, dear snob. It’s been anointed with holy oil of The Library of America. You can now purchase Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep in the fancy schmancy Library of America edition , and place it on your bookshelf in the “C’s” between your Library of America editions of the works of Willa Cather and John Cheever.

As the Atlanta Constitution observed, “The most significant release of the season may well be The Library of America’s two-volume collection of Chandler’s work. In Chandler the pulp crime novel became literature. Chandler’s inclusion in The Library of America honors both the writer and the series.”

As with all great writers, the problem is to choose just one book. Mine is The Big Sleep because it’s even better than the wonderful Bogart/Bacall movie. The Kurtz of The Big Sleep is Rusty Regan, the former I.R.A. guerilla, bootlegger, and special friend of the wealthy General Sternwood. Rusty married Vivian Sternwood, the elder of the General’s two daughters, but has mysteriously disappeared. As in The Heart of Darkness, a man named Marlow–here, a private eye named Philip Marlowe–is hired to find the missing man.

Never mind that the plot itself has, to say the least, a few loose ends. Indeed, when William Faulkner was writing the screenplay for the movie version, he telegraphed Chandler in desperation to find out who actually committed one of the murders in the book, and Chandler telegraphed back that he had no idea.

Never mind. Read this novel for the mood, for the characters, and for the language. Chandler was master of the one-liner — “It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window” — and the extended scene setter. Here’s his description of the greenhouse where Marlowe meets his new client, General Sternwood:

“The air was thick, wet, steamy and larded with the cloying smell of tropical orchids in bloom. The glass walls and roof were heavily misted and big drops of moisture splashed down on the plants. The light had an unreal greenish color, like light filtered through an aquarium tank. The plants filled the place, a forest of them, with nasty meaty leaves and stalks like the newly washed fingers of dead men.”

Ernest Hemingway once wrote that “all modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.” The Los Angeles Times adds the following post-Hemingway perspective:

Raymond Chandler’s prescience may be why, of all the detective novelists, he has exerted the most crossover effect on so-called serious authors. From Charles Bukowski, whose final novel Pulp was a tongue-in-cheek tribute to the hard-boiled genre, to Paul Auster, whose mid-1980s New York Trilogy recast the detective novel from a post-modern point of view, Chandler has cast a long shadow. Indeed, Chandler’s conjoining of the vernacular with literary textures suggests a direction for writers to pursue at a time when traditional methods of storytelling have begun to seem contrived, too fixed and non-fluid to encompass the jarring juxtapositions that make up real life.