As you may have guessed, the topic of this post is a penis. No ordinary penis, either. Indeed, the scene opens like the beginning of a joke: two literary lions walk into a bar in Paris. One will soon confide to the other his concerns about his penis. Specifically, about its size. And the scene will be immortalized in what may well be the apex (or, more accurately, the nadir) of passive-aggressive humiliation in American literature.

But first, some background:

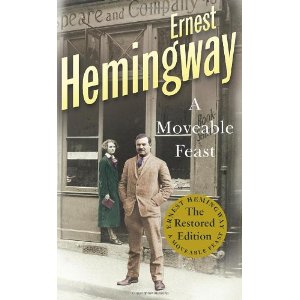

I was browsing in a used bookstore the other day and came across a copy of Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, his classic memoir of Paris in the 1920s, published posthumously in 1964. I first read this beautifully evocative book nearly a quarter of a century ago. And all these years later, I could still remember his depictions of the life of a struggling, young, expatriate journalist  and writer, still madly in love with his first wife, Hadley Richardson. Part of the fun of A Moveable Feast was reading of his encounters with other great artists of that era, including John Dos Passos, Ford Maddox Ford, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas. And, of course, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.

and writer, still madly in love with his first wife, Hadley Richardson. Part of the fun of A Moveable Feast was reading of his encounters with other great artists of that era, including John Dos Passos, Ford Maddox Ford, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas. And, of course, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.

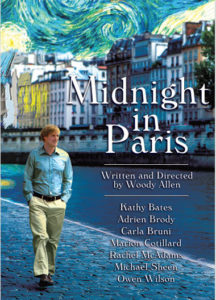

The memoir’s influence continues to this day, having inspired, among other things, Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.  In that film, a nostalgic screenwriter (played by Owen Wilson), while on a trip to Paris with his fiancée’s family, finds himself mysteriously going back to the Paris of the 1920s every day at midnight. Those time-travel portions evoke scenes inspired by the Hemingway memoir, including interactions with Gertrude Stein, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and Hemingway. The Wilson character uses the phrase “a moveable feast” at least twice in the film, and a copy of the book appears in one scene

In that film, a nostalgic screenwriter (played by Owen Wilson), while on a trip to Paris with his fiancée’s family, finds himself mysteriously going back to the Paris of the 1920s every day at midnight. Those time-travel portions evoke scenes inspired by the Hemingway memoir, including interactions with Gertrude Stein, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and Hemingway. The Wilson character uses the phrase “a moveable feast” at least twice in the film, and a copy of the book appears in one scene

But back to F. Scott Fitzgerald. As I walked to the counter to buy the book, I had this vague memory of a bizarre encounter between Hemingway and Fitzgerald in which the topic was the size of Fitzgerald’s penis. And thus when I returned home with my copy of A Moveable Feast, I set aside my higher literary ambitions and instead scanned the table of contents in search of a promising chapter heading. And there it was: Chapter 19, entitled “A Matter of Measurement.”

The chapter opens with Hemingway explaining that Fitzgerald had asked him to meet for lunch at a restaurant. “He said he had something very important to ask me and that I must answer him absolutely truly. I said that I would do the best I could.”

They meet at the restaurant. “We talked about our work and about people and he asked me about people that we had been out of touch with.”

Hemingway keeps waiting “for it to come, the thing that I had to tell the absolute truth about; but he would not bring it up until the end of the meal, as though we were having a business lunch.”

Finally, as they are eating a cherry tart and drinking another carafe of wine, Fitzgerald gets to the point: “Zelda said that the way I was built I could never make any woman happy and that was what upset her originally. She said it was a matter of measurements. I have never felt the same since she said that and I have to know truly.”

What follows next is, well, unique. I’ll let Hemingway take over:

“Come out to the office,” I said. “Or you go out first.”

“Where is the office?”

“Le water,” I said.

We came back into the room and sat down at the table.

“You’re perfectly fine,” I said. “You are O.K. There’s nothing wrong with you. You look at yourself from above and you look foreshortened. Go over to the Louvre and look at the people in the statues then go home and look at yourself in the mirror.”

“Those statues may not be accurate.”

“They are pretty good. Most people would settle for them.”

“But why would she say that?”

“To put you out of business. That’s the oldest way to putting people out of business in the world.”

He takes Fitzgerald over to the Louvre to look at statues, but Fitzgerald remains doubtful, thus triggering the final bit of advice from Hemingway:

“It is not basically a question of the size in repose,” I said. “It is the size it becomes. It is also a question of angle.” I explained to him about using a pillow and a few other things that might be useful for him to know.”

It is an unforgettable scene, with an observation from Hemingway that has no doubt stuck with many male readers: “You look at yourself from above and you look foreshortened.”

But when I closed the book I found myself thinking about what Hemingway had done. As a lawyer by day, I would describe the contents of that chapter as an indisputable (and despicable) invasion of privacy. One can hardly imagine a more private, painful, and embarrassing disclosure than the one Fitzgerald shared with Hemingway, and which Hemingway then shared with the world.

Often, when I see a Shakespeare play or watch a movie version of a Jane Austen novel, I find myself hoping that there is indeed an afterlife so that Shakespeare and Austen and all of the other artists, many whom died, like Herman Melville, in obscurity, can bask in the heavenly glory of their immortal art.

But when I closed the book after reading Chapter 19, I found myself hoping that, at least for F. Scott Fitzgerald, who died years before publication of A Moveable Feast, there is no afterlife.